Shoshana Zuboff • June 7, 2019

George Orwell repeatedly delayed crucial medical care to complete 1984, the book still synonymous with our worst fears of a totalitarian future — published 70 years ago this month. Half a year after his novelʼs debut, he was dead. Because he believed everything was at stake, he forfeited everything, including a young son, a devoted sister, a wife of three months and a grateful public that canonized his prescient and pressing novel. But today we are haunted by a question: Did George Orwell die in vain?

Orwell sought to awaken British and U.S. societies to the totalitarian dangers that threatened democracy even after the Nazi defeat. In letters before and after his novelʼs completion, Orwell urged “constant criticism,” warning that any “immunity” to totalitarianism must not be taken for granted: “Totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere.”

Since 1984ʼs publication, we have assumed with Orwell that the dangers of mass surveillance and social control could only originate in the state. We were wrong. This error has left us unprotected from an equally pernicious but profoundly different threat to freedom and democracy.

For 19 years, private companies practicing an unprecedented economic logic that I call surveillance capitalism have hijacked the Internet and its digital technologies. Invented at Google beginning in 2000, this new economics covertly claims private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. Some data are used to improve services, but the rest are turned into computational products that predict your behavior. These predictions are traded in a new futures market, where surveillance capitalists sell certainty to businesses determined to know what we will do next. This logic was first applied to finding which ads online will attract our interest, but similar practices now reside in nearly every sector — insurance, retail, health, education, finance and more — where personal experience is secretly captured and computed for behavioral predictions. By now it is no exaggeration to say that the Internet is owned and operated by private surveillance capital.

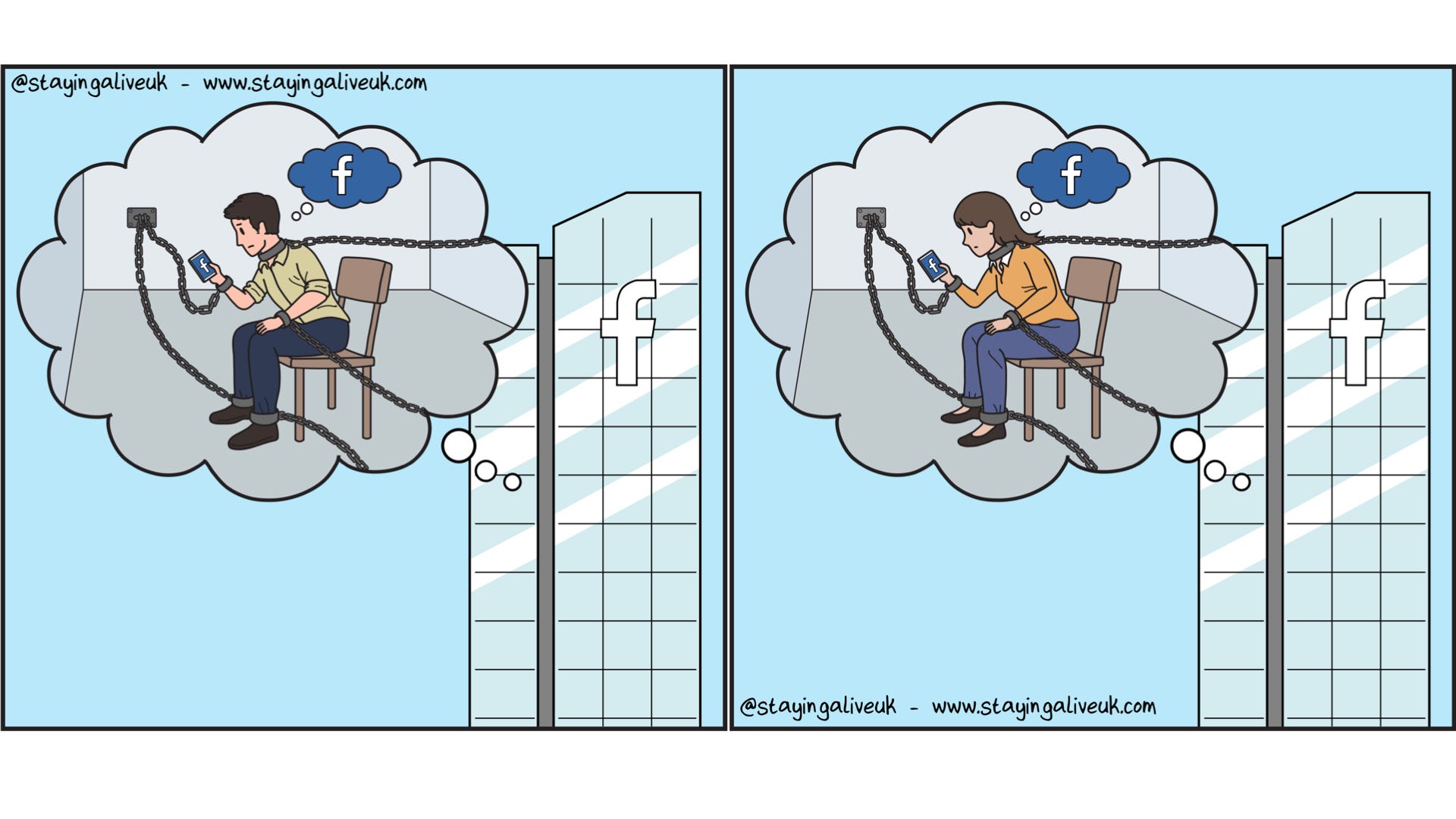

In the competition for certainty, surveillance capitalists learned that the most predictive data come not just from monitoring but also from modifying and directing behavior. For example, by 2013, Facebook had learned how to engineer subliminal cues on its pages to shape usersʼ real-world actions and feelings. Later, these methods were combined with real-time emotional analyses, allowing marketers to cue behavior at the moment of maximum vulnerability. These inventions were celebrated for being both effective and undetectable. Cambridge Analytica later demonstrated that the same methods could be employed to shape political rather than commercial behavior.

Augmented reality game Pokémon Go, developed at Google and released in 2016 by a Google spinoff, took the challenge of mass behavioral modification to a new level. Business customers from McDonalds to Starbucks paid for “footfall” to their establishments on a “cost per visit” basis, just as online advertisers pay for “cost per click.” The game engineers learned how to herd people through their towns and cities to destinations that contribute profits, all of it without game playersʼ knowledge.

Democracy slept while surveillance capitalism flourished. As a result, surveillance capitalists now wield a uniquely 21st century quality of power, as unprecedented as totalitarianism was nearly a century ago. I call it instrumentarian power, because it works its will through the ubiquitous architecture of digital instrumentation. Rather than an intimate Big Brother that uses murder and terror to possess each soul from the inside out, these digital networks are a Big Other: impersonal systems trained to monitor and shape our actions remotely, unimpeded by law.

Instrumentarian power delivers our futures to surveillance capitalismʼs interests, yet because this new power does not claim our bodies through violence and fear, we undervalue its effects and lower our guard. Instrumentarian power does not want to break us; it simply wants to automate us. To this end, it exiles us from our own behavior. It does not care what we think, feel or do, as long as we think, feel and do things in ways that are accessible to Big Otherʼs billions of sensate, computational, actuating eyes and ears.

Instrumentarian power challenges democracy. Big Other knows everything, while its operations remain hidden, eliminating our right to resist. This undermines human autonomy and self- determination, without which democracy cannot survive. Instrumentarian power creates unprecedented asymmetries of knowledge, once associated with pre- modern times. Big Otherʼs knowledge is about us, but it is not used for us. Big Other knows everything about us, while we know almost nothing about it. This imbalance of power is not illegal, because we do not yet have laws to control it, but it is fundamentally anti-democratic.

Surveillance capitalists claim that their methods are inevitable consequences of digital technologies. This is false. Itʼs easy to imagine the digital future without surveillance capitalism, but impossible to imagine surveillance capitalism without digital technologies.

Seven decades later, we can honor Orwellʼs death by refusing to cede the digital future. Orwell despised “the instinct to bow down before the conqueror of the moment.” Courage, he insisted, demands that we assert our moral bearings, even against forces that appear invincible. Like Orwell, think critically and criticize. Do not take freedom for granted. Fight for the one idea in the long human story that asserts the peopleʼs right to rule themselves. Orwell reckoned it was worth dying for.

Contact us at editors@time.com.

TIME Ideas hosts the world's leading voices, providing commentary on events in news, society, and culture. We welcome outside contributions. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editor